In response to SFUSD school closures the Asian Art Museum is expanding free admission on Mondays, Thursdays and Fridays.

All Articles

Sarah Rifky is co-founder of Beirut, an art initiative in Cairo, and founder of CIRCA (Cairo International Resource Center for Art).

In her essay “Choreographies of Protest,” Susan Leigh Foster offers a compelling framework for understanding collective political action.[i] Protest, she argues, is not only expressive but choreographic: Bodies are arranged in space and time with intention, forming patterns that unsettle the expectations of order and authority. This reading opens a deeper question: If protest is choreography—deliberate movement that speaks against power—then where does that leave dance?

Thinking alongside Rave Into the Future—an exhibition curated by Naz Cuguoğlu and still becoming as I write—dance no longer resides on the fringes of entertainment. It becomes a charged terrain for negotiating presence, power, and relation. As a language of collective resistance, it is practiced, remembered, sustained. What protest sets in motion, dance carries forward—drawing bodies together, cultivating rhythm amid constraint, opening forms of solidarity that do not rely on speech. It lingers when gatherings are broken up, when language falters, when joy is suspect. Where state power scripts the tempo of daily life, dance reclaims time—slipping the beat, veering off count, refusing containment.

This essay considers how contemporary artists from West Asia and its diasporas engage with dance as a conceptual, political, and sonic framework. The works in this exhibition unfold across installations, videos, performances, and speculative environments in which movement—sometimes direct, sometimes ambient—becomes a generative force. These artists don’t just show dance; they construct the terms through which bodies gather, move, and push back. Some works foreground the dancing body. Others trace the aftermath of movement, its echoes and residues. All share a concern with how rhythm, gesture, and repetition create the possibility of collective orientation in disorienting times. Implied within many of these practices is the sonic terrain shaped by Fatima Al Qadiri, whose compositions trouble linearity and genre and instead propose a sensory environment in which displacement, desire, and distortion converge. Her music forms both the literal and conceptual atmosphere of several works discussed here, offering a vocabulary for listening to what is unspoken but deeply felt.

This inquiry moves through artistic practices that position dance not as an escape from politics but as a mode of inhabiting and contesting it. Dance leaves its mark as a pulse, as a medium of coded dissent. It reclaims space, enacts alternative temporalities, and marks the body as both vulnerable and powerful. Through these gestures—private and public, grounded and speculative—artists articulate a politics of movement attuned to the urgencies of survival, freedom, and future making.

These movements do not remain in the past, nor do they serve simply as folkloric reminders of resistance. They continue to animate the present, threading together geographies and generations through embodied memory. In 2019, during the Lebanese uprising, protestors transformed Martyrs’ Square in Beirut into a techno rave. Rather than respond to state violence with solemnity, they assembled in rhythm—moving to bass-heavy beats and holding banners that read: “Techno unites us.” The dance floor, in this moment, was not an escape but a reconfiguration of public space, a reassertion of collectivity in a landscape marked by fragmentation and fatigue. The choreography of the protest became a refusal to relinquish joy, a method of staying present without conceding to despair.

Dance does not disappear when it is forbidden. It shifts registers—becomes quieter, more private, more spectral—but it continues to circulate. Across contexts, it operates as a form of continuity under pressure: carrying what must be preserved, rehearsing what cannot yet be spoken aloud, and embodying a kind of knowledge that resists containment. In movement, bodies refuse to forget.

[i] Susan Leigh Foster, “Choreographies of Protest,” Theatre Journal 55, no. 3 (2003): 395–412.

Thinking through dance means staying with the body—its memory, its resistance, its interruptions. Movement does not simply illustrate an idea, nor does it necessarily announce its politics overtly. Its force lies in the way it shapes relations, reorganizes space, and carries affect across bodies, often without language. In this way, dance participates in the work of meaning making that is inseparable from conditions of power, intimacy, and survival.

Barbara Browning has described certain forms of dance, particularly those emerging from diasporic and postcolonial contexts, as vehicles of what she terms “infectious affect.”[i] What interests her is not performance as spectacle but the way rhythm and gesture generate a shared sensibility that bypasses linguistic explanation. Dance becomes a mode of transmission—of history, of trauma, of joy—that travels between bodies, sometimes unnoticed by those invested in more legible forms of resistance. In Browning’s view, dance not only reflects a cultural or political moment, it also reshapes how that moment is lived, how it is absorbed into the nervous system, how it reverberates.

This attention to embodiment as a political field finds resonance in Foster’s theory; her concept of the choreography of protest insists on the spatial and somatic dimensions of collective action. The occupation of a plaza, the coordinated pacing of a march, the rhythmic insistence of a sit-in—all these interventions rely on the expressive capacity of the body to reorganize the visual and spatial order of the state. Foster draws attention to the ways in which protest operates choreographically, arranging bodies in ways that disrupt the flow of capital, reroute authority, and foreground presence where erasure is the norm. The protest, in this formulation, becomes an embodied argument—felt, seen, and enacted.

For Browning and Foster, dance theorizes through proximity, rhythm, occupation. The works in this exhibition extend that thinking, treating glitter, glitch, and vibration not as embellishments but as arguments. Dance is not simply the aesthetic residue of political struggle but part of its infrastructure. It intervenes in time, disturbs the legibility of space, and activates modes of relation that exceed what institutions can script. Within the practices around which this exhibition—and subsequently this essay—evolves, dance functions less as performance and more as atmosphere; and also an archive, a method for thinking and moving through crisis. Its political charge is rarely declarative. It builds slowly, accumulates through repetition, proximity, and resonance, asking us to stay with its complexity rather than reduce it to a single readable act.

[i] Barbara Browning, Infectious Rhythm: Metaphors of Contagion and the Spread of African Culture (New York: Routledge, 1998).

Some gestures begin in silence. They form slowly, behind closed doors, in low-lit spaces of repetition and play. Dance, in these settings, is not choreographed for an audience; it is practiced in fragments, in pauses, in sidelong glances. The body learns to anticipate refusal long before it encounters it. The room becomes a kind of studio, less a space of spectacle than of survival.

In For Your Eyes Only, Yasmine Nasser Diaz reconstructs the bedroom of a Yemeni American girl growing up in 1990s Los Angeles. The installation is lush with contradictions: pop-culture posters layered beside protest flyers, scented stationery arranged with militant precision, intimacy arrayed as architecture. The space evokes both nostalgia and constraint. On an adjacent screen, young women move through private routines—dancing for their own reflection, for the friend behind the camera, for no one at all. Their movements are tentative and self-assured, mundane and mythic. Within this room, the choreography emerges through habit, through the quiet insistence of embodiment practiced daily under pressure. The dance is an extended rehearsal for the kinds of freedom that require practice long before they are lived.

Joe Namy’s Disguise as Dancefloor introduces another site of rehearsal—less private, but no less intimate. A copper floor, conductive and resonant, is installed as both invitation and record. Bass lines vibrate through the metal, meeting the feet of those who enter. The floor holds each step as residue, each vibration as a trace. It doesn’t merely mark presence; it gathers it. Copper, used in wiring and circuitry, becomes a medium not just for sound but for collective memory. The dance floor registers energy—of protest, of joy, of endurance. It does not erase what came before; it responds, layering movement and rhythm into an archive felt through the soles of the feet.

Sahar Khoury’s sculptures transmit sound in another register, drawing from familial archives and regional histories. In one work, the inimitable voice of the Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum drifts through the structure, accompanied by recordings that are at once personal and shared: a great aunt’s murmur, a radio playing in the kitchen, fragments of song woven through daily life. The installation becomes a transmitter, carrying the textures of feminist memory across time. These transmissions do not operate within conventional categories of documentation. They linger as atmosphere, reverberating through material forms that listen as much as they speak.

In the work of these artists, dance extends beyond the visible. It is embedded in preparation, in vibration, in the layered histories carried through space. These aren’t performances in the traditional sense but systems of attunement—ways of organizing attention, feeling, and resistance through the body and its environments.

Where movement is punished, imagination becomes a rehearsal space. Artists working with myth, with the jinn, with speculative geographies and temporal folds are able to augment reality. They mine the strange, the slippery, the supernatural for its political charge. Within these works, dance becomes a medium for haunting, for irreverent joy, for queerness in motion.

In Um Al Naar (Mother of Fire), Farah Al Qasimi introduces a jinni who is neither villain nor moral lesson but a mischievous matriarch—a figure of misbehavior, glamour, and impossible visibility. Played by the artist herself in glittering garments and mirrored rooms, Um Al Naar evades containment, folding folklore and pop culture into a single flickering performance. She dances in fragments, tossing her hair in slow motion, swaying with a nonchalance that feels both private and exaggerated. This is not a spectacle made for consumption but a choreography that asserts female embodiment as opaque, playful, and undomesticated. The hair dance, in particular, functions as both ritual and refusal—claiming pleasure on the artist’s terms in a space that is already encoded with surveillance, modesty, and colonial suspicion. The jinni becomes an avatar of feminine unruliness, drawing from oral storytelling and Gulf futurism to mark another kind of presence: one that will not be easily translated.

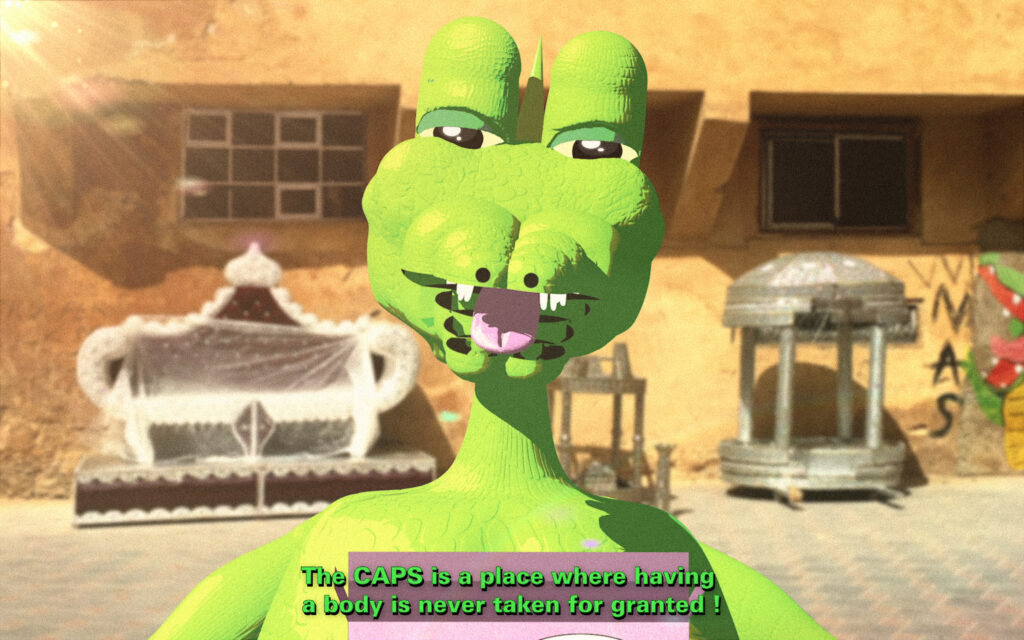

Meriem Bennani’s Party on the CAPS is set in a near-future borderland where refugees, criminals, and the undocumented are exiled to a floating island surveilled by drones and patrolled by invisible bureaucracies. The world is absurd, high-gloss, disorienting. Yet the absurdity absolutely does not dilute its politics; rather, it intensifies them. Amid the chaos, people dance, they party. The island becomes a kind of floating rave, where strobe lights interrupt the violence and humor refracts the carceral. The characters—sometimes green, rendered, exaggerated, magical, full of swagger—move through this dystopia with grace and gallows humor. Their dancing becomes a form of endurance, a refusal to be flattened by narrative. Bennani doesn’t resolve the contradiction between joy and confinement; she stages it. The rave is the site where friction turns kinetic, socially and politically.

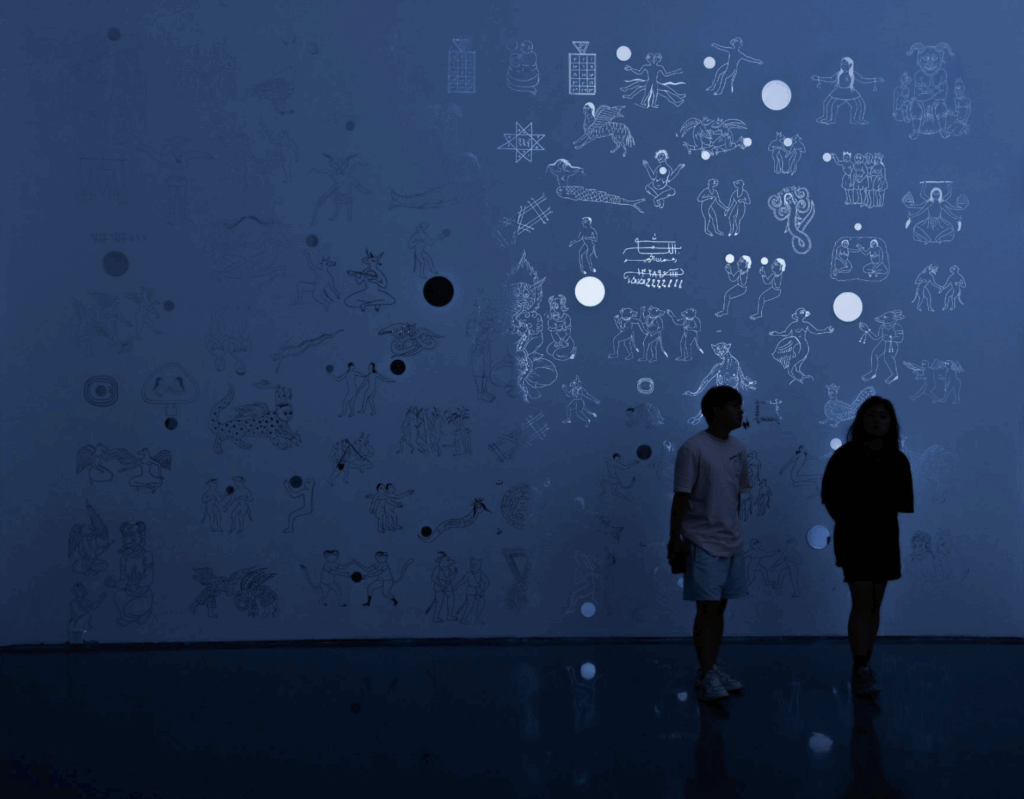

In She Who Sees the Unknown: The Queer Withdrawings, Morehshin Allahyari turns to myth as a speculative technology. Her mirrored figures, conjured in reflective surfaces and layered video, perform ritual gestures that never settle into certainty. The queer body becomes unfixed—refracted, multiplied, unreachable. Dance appears not as choreography but as tempo: slow, hypnotic, deliberate. These gestures are not declarations; they are incantations. Allahyari assembles them from Persian mythologies and contemporary queer politics, collapsing the timeline between ancient and reenchanted worlds. Reflection becomes a site of multiplicity: what is seen and what remains hidden, what is mirrored and what escapes capture. The ritual becomes queer not because it announces identity but because it destabilizes the frame altogether. Within this space, dance is less an act of visibility than one of endurance and transformation.

Tavia Nyong’o reminds us that queerness does not simply anticipate a better future; it rehearses the refusal of the now.[i] His writing on Afro-fabulation and the aesthetics of Black performance offers a lens through which to consider how dance, especially in diasporic and speculative registers, stages rupture without resolution. Within the Gulf futurist imaginary, this becomes palpably clear. The glitch, the shimmer, the haunted bass line all act as tactics of withdrawal and invention. They are not oriented around arrival but toward an elsewhere always in rehearsal. These artists do not offer blueprints for liberation. Instead, they propose atmospheres of unruliness, where bodies stretch across time signatures, where refusal is improvised in movement and noise. The future, here, is not deferred—it is unsettled, looped, refracted into a space of potential that resists capture.

[i] Tavia Nyong’o, Afro-Fabulations: The Queer Drama of Black Life (New York: New York University Press, 2018), 14.

Gulf futurism unfolds in a terrain shaped by contradiction. It is not born from the linear promises of technological advancement, nor does it rest in the comfort of cultural nostalgia. Instead, it arises from their collision—the point where the steel and glass of hypermodernity presses against the lingering dust of Bedouin cosmology, and where the language of progress is spoken in a dialect infused with loss, surveillance, and performance.

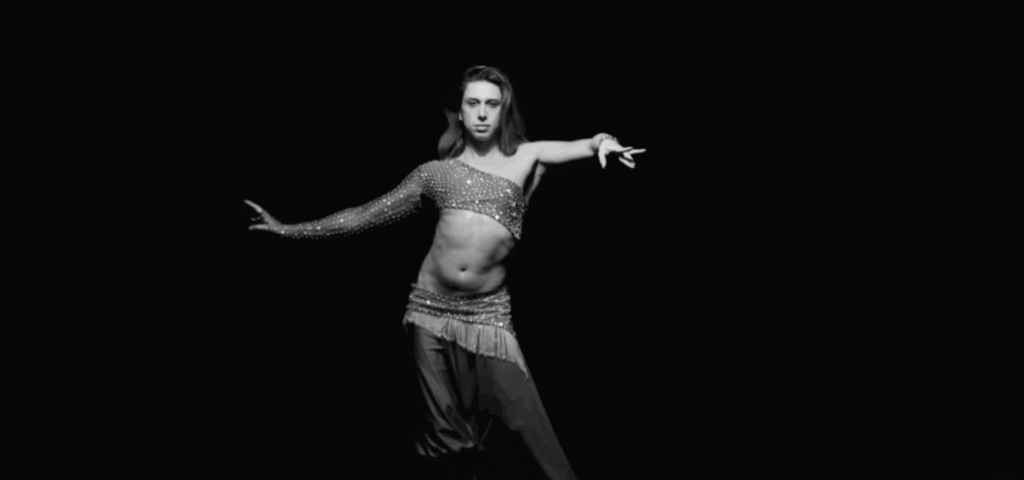

The work of Sophia Al-Maria and Fatima Al Qadiri—both iconic artists—maps this terrain with precision and distortion. Their collaborative project Spiral spins outward from the body—its movement, its mediation, its amplification. The figures that appear are unstable, refracted through screens and soundscapes, gendered and degendered by light, rhythm, and rhythm’s failure. In Al-Maria’s visual worlds and Qadiri’s sonic ones, the body dances in ways that complicate recognition. There is a trace of the belly dance, yes, but it arrives decontextualized, slowed, queered, embedded in a synthetic pulse—a choreography assembled from fragments of cultural memory and global fantasy, built to endure repetition and rupture. I would venture to say there is nothing ironic about their practice. These gestures circulate within a sonic imaginary that does not seek resolution. Qadiri’s low-frequency rhythms resonate in the diaphragm and sternum, asserting physical presence without articulating narrative. The bass behaves like an undercurrent—it doesn’t carry the melody, it unsettles it. Fractures in timing, breakdowns in structure, and loops without clear progression produce a kind of dissonant intimacy. The sound doesn’t invite you into a future; it surrounds you with the vestiges of possible ones, failed or deferred. There is movement here, but not in the direction one expects.

What emerges through this aesthetic is less a celebration of futurity than a confrontation with its exhaustion. Al-Maria’s notion of Gulf futurism does not promise arrival; it lingers in stalled infrastructures, in the aesthetics of waiting, in the absurdity of opulence paired with repression. The future appears not as a promised arrival but as a warped zone distorted by the weight of the present. On these dance floors, bodies rehearse themselves, and gender is stretched across registers. Movement becomes a tool for sensing conditions that cannot be named directly. The bodies themselves expand the discourse. Something resists becoming legible to the systems that seek to contain it.

There’s a particular kind of aftermath that refuses to disappear. It clings to the soles of shoes, embeds itself in carpet fibers, reappears weeks later on someone’s cheek or collarbone. Glitter, for all its frivolous reputation, is stubborn. It marks what has happened long after the event has ended. In :mentalKLINIK’s Puff Out M_2205_pink, this refusal becomes material.

The installation stages excess: smoke machines, strobe lights, sequins, and sound—all calibrated to misbehave. It draws on the aesthetics of the rave but removes the crowd. What remains is aftermath, a scene stripped of bodies yet heavy with their implication. Glitter circulates in the air and across the floor, refusing containment. It is beautiful, but not clean. It resists the protocols of institutional tidiness, leaking past boundaries, rendering the white cube porous. What :mentalKLINIK performs here is the excess of dance’s spectacle—the mess that outlives performance, the trace that escapes curatorial grasp.

Raving, in this context, becomes a ritual of scattering. There is no singular choreography to follow, no sequence to memorize. The movement is collective, nonlinear, unstable. It spills and returns. The body in motion leaves behind more than sweat and breath; it leaves atmosphere, accumulation. The glitter becomes indexical, not to the self but to proximity—to having been with, moved besides, vanished into. In this, :mentalKLINIK draws out a politics of residue: that which resists cleaning, survives translation, continues to shimmer after silence has fallen. There’s something irreverent in this aesthetic—joy as spillage, refusal as sparkle. But it’s also deeply architectural. The work speaks to how institutions attempt to stage, frame, and contain joy, only to find it leaking through the cracks. It’s an impossible material to archive, this excess. And yet it endures, sticking to walls, to policies, to the backs of knees.

In Puff Out M_2205_pink, the aftermath is not an ending. It is what gathers in the corners. It is what carries forward, attaching itself to those who witnessed, those who danced, even those who stood still. The work insists that movement does not vanish when the music stops. It lingers—in the energy, the vibration, in bodies altered by proximity to one another.

Dance, across these works, emerges as method—a fragile infrastructure for freedom in rehearsal. In bedrooms and backrooms, in speculative geographies and broken architectures, the body moves—not to forget, but to remember otherwise. These gestures don’t sidestep the political, nor do they charge at it head-on. They inhabit it otherwise—through atmosphere, through repetition, through the kinds of movement that unsettle precisely because they don’t declare their intent. They draw on lineages of survival, where movement was often the only archive available.

Across this constellation of artists, dance appears not as choreography imposed from above but as knowledge formed in friction—with sound, with surface, with constraint. These spaces—copper floors, pink sanctuaries, exilic nightclubs—hold the beat in glitch and shimmer. What began as movement becomes memory, encoded in repetition. It insists that repetition, when inhabited with care and collectivity, is not stagnation but strategy.

This is not a return to joy as palliative. The joy that circulates here is charged. It is risked. It is built with and for others. It stains the floor. It enters the lungs. It holds the weight of what cannot yet be spoken. These movements are structural. They rewire the senses. They reconfigure space. They draw maps across generations, where transmission happens not only through words but through gesture, pulse, and breath.

If protest can be choreographed, as Foster suggests, then dance can be a form of protest long before it takes to the street. It is a method for dreaming under surveillance, for touching across distance, for refusing what has been assigned. This essay has traveled through rooms, rituals, rave floors, screens, towers, myths, and mess to follow the movement that insists on being more than momentary. The invitation remains open—it asks us to move, to attune differently, to notice what builds beneath the surface. What gathers there is not ephemeral. It is the next movement, already rehearsing itself in shadow and shimmer.