An essay by Naz Cuguoglu, Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art

“You are not censors but sensors, not aesthetes but kinaesthetes. You are sensationalists. You are the newest mutants incubated in wombspeakers. Your mother, your first sound. The bedroom, the party, the dancefloor, the rave: these are the labs where the 21st C nervous systems assemble themselves, the matrices of the Futurhythmachinic Discontinuum. The future is a much better guide to the present than the past. Be prepared, be ready to trade everything you know about the history of music for a single glimpse of its future.” — Kodwo Eshun[i]

I remember a dance floor, not just for what it was, but for what it allowed us to imagine. In the haze of strobe and bass, we built worlds. We mourned what we’d lost and rehearsed what might come next. That is the feeling this exhibition chases: not nostalgia, but the radical potential of joy in motion.

Rave Into the Future is a love letter to the dance floor as a portal, a site of speculative world-building shaped by diasporic longing, collective resistance, and pleasure. Here, sound becomes memory, movement becomes language, and the future pulses just beneath our feet. The exhibition creates a sonic space for “counterpublic” and “undercommon” communities imbued with displacement, memory, and hope.[ii] It gives agency to vibration—sonic, spatial, emotional—letting waves of belonging move through our flesh. The exhibition unfolds across a series of stages, including the dance floor, the podium, the chill room, and the afterparty, echoing the temporal and emotional arc of the rave itself.

[i] Kodwo Eshun, More Brilliant than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction (London: Quartet, 1998), 00[-0011].

[ii] I borrow the term “undercommons” from Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (New York: Minor Compositions, 2013), and “counterpublics” from Nancy Fraser, “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy,” Social Text 25–26 (1990): 56–80.

Sonic vibrations hold potential and possibility. We encounter an alternative form of collaboration in the politics of grooving. This collective joy echoes Barbara Ehrenreich’s framing of dance as a force of social cohesion and resistance.[i] It’s all about how the bass feels: energetic, dynamic, and caressing. The bass teaches us the act of deep listening. This low frequency shakes us as we dance beyond temporal possibilities. Moving walls, floors, whole structures, piercing through our bodies, the bass makes liberation possible. For a moment, we stop being who we are. In that moment, we redefine hierarchy and hegemony—a moment of anticolonial potential, as Katherine McKittick writes.[ii] Dancing to the bass, especially in community, demands a generous mode of being, an openness. As McKittick notes, “These places to dance, listen, and share are physiological-creative expressions that undo and resist the racially coded belief system.”[iii] In the rave space, that system (one that has historically exoticized, pathologized, or silenced diasporic bodies) is momentarily interrupted. Here, dancers transmute sonic textures into collective strategies of refusal. Grooves and waveforms carry alternate narratives, where identity is not imposed from the outside but shaped through joy, movement, and shared futurity.

At the heart of the exhibition, Joe Namy’s 100-square-foot copper dance floor grounds these ideas in material form (fig. 1). Copper, a material historically prized for its conductivity, becomes here a conduit for the energy of collective movement. Every scuff, step, and trace leaves its imprint, turning Disguise as Dancefloor into a living archive of those who gather upon it. This focus on infrastructures of gathering continues in Sahar Khoury’s commissioned installation, which features a working DJ deck built atop reconfigured animal cages—structures once used for confinement, now repurposed as stages for improvisation and togetherness. Khoury’s gesture subtly invokes broader systems of containment that mark migrant and racialized bodies, especially under regimes of surveillance and exclusion. In Khoury’s hands, the cage becomes a platform for collective healing.

[i] Barbara Ehrenreich, Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy (New York: Metropolitan, 2006).

[ii] Katherine McKittick, “Knocked Out,” in Steve McQueen: Bass, ed. Donna DeSalvo et al. (New York: Dia Art Foundation, 2024).

[iii] McKittrick, “Knocked Out,” 93.

How does sound become a vessel for diasporic memory, longing, and resistance across generations? Our ancestral time demands us to dance to what has been danced to before. We remember the memories of dancing together. We gather and feel alright, carried by the waves of the “oceanic rave,” where sound moves like water.[i] The diasporic subject often inherits a tendency toward self-erasure or shrinking.[ii] The rave space, by contrast, offers a refuge that lives in noise—and it’s intergenerational. It makes belonging possible in a foreign land. As a refusal of silence and smallness, the rave space collects stories of migration.

As many have observed, the rave is for those who are not welcomed elsewhere.[iii] It is a safe space for Blackness, queerness, the marginalized.[iv] It makes possible the feeling you get when you are amongst your people. Above all, it centers joy—a joy not overshadowed by poverty or aggression (as is often the preferred narrative of the mainstream). It is a space for desires, a space to heal and grieve. The rave space makes it possible for diasporic bodies to engage in “pleasure activism.”[v] Though histories of trauma often sever desire from the diasporic experience, here that desire becomes transformative. “Love heals,” as bell hooks reminds us.[vi]

As a carrier of memory, the rave space is diasporic—it holds room for the improvisational and the in-between. Many artists in the exhibition navigate this space of transmission. Another work by Sahar Khoury, a twenty-foot-tall installation reminiscent of a radio tower, pays tribute to the legendary Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum (fig. 2). It features a commissioned sound piece by Lara Sarkissian and Esra Canoğulları (8ULENTINA) that reimagines a live performance of Kulthum’s “Al Atlal” (The ruins) layered with an archival recording of Khoury’s late aunt singing at a family gathering. More than a monument; it extends private memory into public space, tuning grief and ancestral resonance to a shared frequency.

Maryam Yousif’s commissioned ceramic sculpture—an oversized cassette tape presented on a stage with palm trees, honoring the Assyrian artist Juliana Jendo—extends this ethos. Jendo’s songs in Turoyo and Chaldean Neo-Aramaic transform endangered languages into sonic monuments, channeling resilience and intimacy across generations. Both works operate as nodes in a collective transmission, carrying diasporic sound and memory into the future.

[i] I borrow the term “oceanic wave” from McKenzie Wark, Raving (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2023).

[ii] Édouard Glissant writes, “For Caribbean man … noise is essential to speech,” emphasizing how oral cultures resist the colonial demand for silence and order. In this context, the rave becomes a space where diasporic subjects unlearn self-erasure through collective noise and expressive presence. See Édouard Glissant, Caribbean Discourse: Selected Essays (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1989).

[iii] McKenzie Wark, “Civilization and Its Discotheques,” in Writing on Raving, ed. Geoffrey Mak et al. (New York and London: OR Books, 2025).

[iv] Here it is important to note the complexity of the term “safe space.” While often evoked as an ideal, it can obscure the tensions, negotiations, and exclusions that happen within such spaces. For a deeper discussion of these contradictions, see Luis Manuel Garcia-Mispireta, Together, Somehow: Music, Affect, and Intimacy on the Dancefloor (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2023).

[v] For more on this concept, see Adrienne Maree Brown, Pleasure Activism (Edinburgh: AK Press, 2019).

[vi] bell hooks, All About Love: New Visions (New York: Morrow, 2000), 209.

The dance floor offers a glimpse of a better world: a space of self-invention, transformation, and connection. This speculative impulse reflects José Esteban Muñoz’s “queer futurity,” a call to imagine and enact better pleasures and other ways of being.[i] The dance floor suggests a way of living that is more caring. For marginalized groups, it provides a utopian vision of equal belonging.[ii] As the night turns to dawn, the first light becomes a metaphor for hope. Rave space is about the political importance of daydreaming and imagining other possible worlds. Graham St John writes, “Technotribes are often critical of the past, dissatisfied with the present and involved in the efforts to reclaim the future.”[iii]

As a ritual, the bodily copresence that unfolds on the dance floor provides a space of solidarity. Drawing from queer and feminist theories, the dance floor can be understood as a counterpublic, a site where marginalized bodies forge new intimacies and kinships outside the norms of heteronormative, racialized, or capitalist social contracts. It becomes a space not only of refusal but of world-making, where collectivity and pleasure are reclaimed as political acts. Though the sound may begin with a single track, beat, or gesture, it reverberates outward, filling the space, forging subterranean connections, and bridging bodies in motion. And in that moment, the dancers give agency to the sound. “What happens when,” as Roshanak Kheshti asks, “the intellectual chooses the dance as a site of knowledge production?”[iv] It’s a different sort of knowledge, a way of knowing through feeling. As dancers fall into sync, they begin to move in resonance, each body attuned to the other, guided by the pulse.

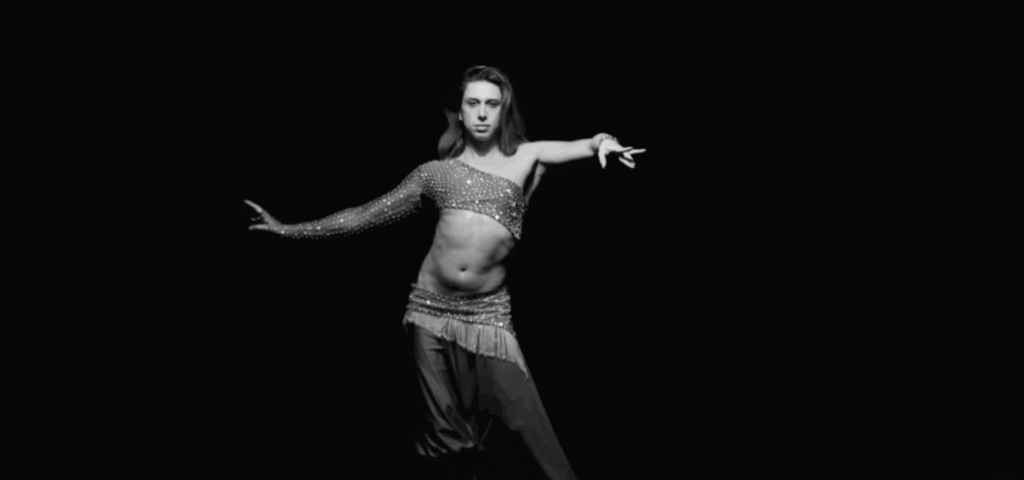

Sophia Al-Maria and Fatima Al Qadiri’s collaborative work Spiral visualizes this bodily copresence (fig. 3). As the artists who coined the term “Gulf futurism,” they imagine a future where diasporic and queer bodies move freely, unburdened by Orientalist projections or cultural erasure. In Spiral, the dancers Zadiel Samsaz and Eli El Sultan engage in a belly dance–off that evolves into a contemporary and sensual homage to the traditional form. Long entangled with Orientalist fantasies and exoticized representations, the belly dance has often been stripped of its cultural depth and reduced to spectacle. Here, it is reclaimed and recharged, reinscribed with defiance, body positivity, and unbridled queer joy. Al Qadiri’s track “Shaneera” functions as the soundtrack to the exhibition, imagining what the future of queer Arabic dance music could sound like.

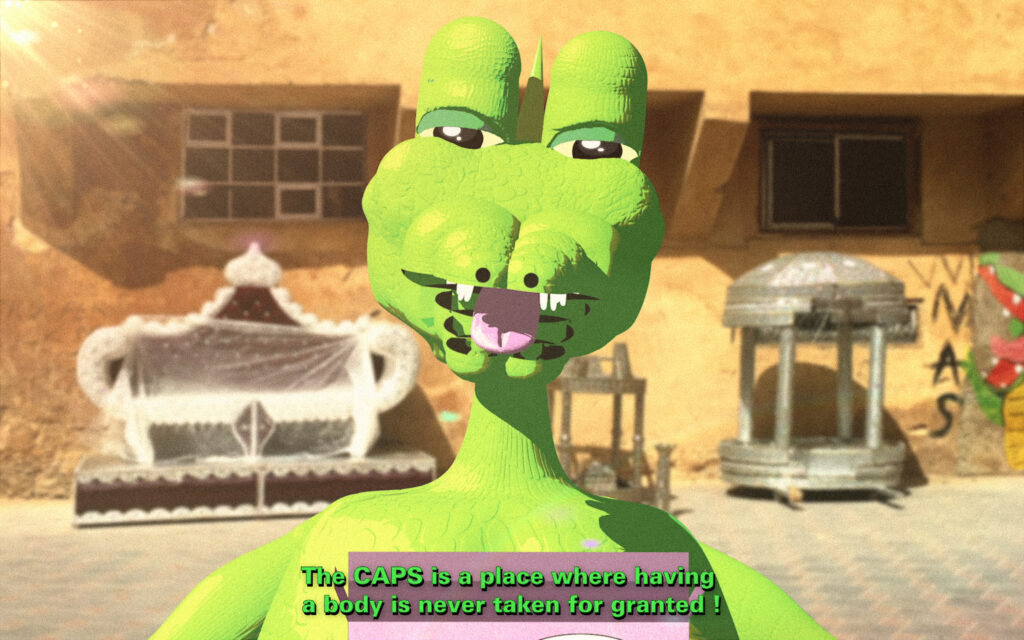

This speculative energy, rooted in movement as resistance and futurity, continues in the work of Meriem Bennani (fig. 4). Her vision of the future honors communal resilience, humor, and the refusal to be confined by essentialist ideas of identity and culture. Her video Party on the CAPS follows Fiona, a chatty crocodile, through a futuristic island refugee camp where teleportation has replaced air travel. The story unfolds at a birthday party in the Moroccan quarter of the CAPS filled with drumming, dancing, and a rapping MC, offering a surreal but tender portrait of cultural continuity.

[i] José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: New York University Press, 2009),

[ii] For a more expansive history of rave culture, from drag balls to Detroit, and its entanglements with both dystopian futurescapes and utopian Afrofuturism, see Garcia-Mispireta, Together, Somehow.

[iii] Graham St John, “Post-Rave Technotribalism and the Carnival of Protest,” in The Post-Subcultures Reader, ed. David Muggleton and Rupert Weinzierl (Oxford: Berg, 2003), 78.

[iv] Roshanak Kheshti, “Pocodisco: The Sonic Performativity of Grief, Grievance, and Joy in Diaspora,” American Anthropologist 126 (2024): 272, https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.13884.

At a rave, time stretches: “The time where there is more time” writes McKenzie Wark.[i] Between yesterday and tomorrow, dancers reclaim time from capitalist productivity and bend it toward their own desires. This “labyrinthine time” offers not just transcendence but the seeds of underground revolution.[ii]

Breaking the linearity of time and celebrating the collective nature of the dance floor are the works by Farah Al Qasimi and Morehshin Allahyari. An homage to all the ghosts of the dance floor, the video Um Al Naar (Mother of Fire) by Al Qasimi centers on a jinn (a supernatural spirit) who, fearing her fading relevance, reasserts herself as a vital presence within her community (fig. 5). She does so by dancing alongside women, using her body as a site of self-governance and resilience. Projected on wallpaper that evokes a rave-lit living room, the work is accompanied by photographs of khaleeji hair dancers.[iii] Presented alongside images of mouths frozen in eternal screams, the installation becomes a gesture of cathartic release.

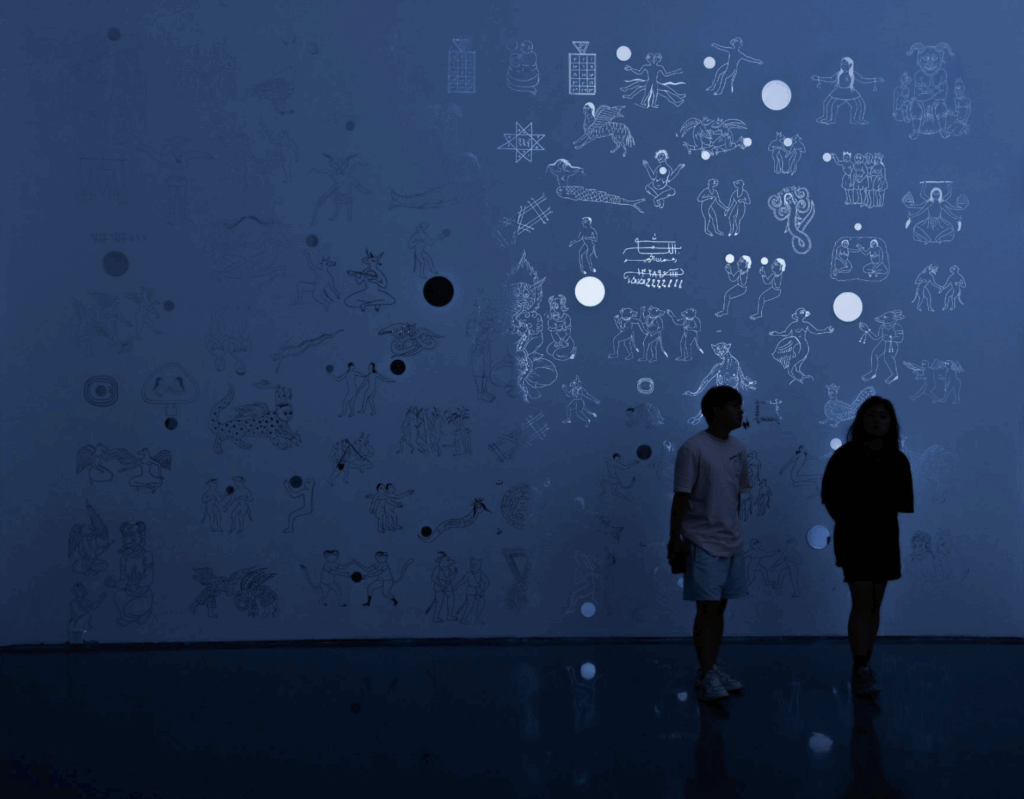

Allahyari’s installation, She Who Sees the Unknown: The Queer Withdrawings, draws on Islamic mythology and the intricate mirrorwork found in Iranian shrines and features reflective surfaces that animate a dance of mythical figures (fig. 6). Rooted in an archive of manuscripts, the work conjures a space of queer gathering and ritual. Two sculptures, Qareen I and Qareen II (in Islamic belief, a qareen is a constant companion or spiritual double), stand as protectors and healers, watching over this space of transformation and care.

[i] Zoë Berry, “Seedlings,” in Writing on Raving, ed. Geoffrey Mak et al. (New York and London: OR Books, 2025), 120.

[ii] I borrow the term “labyrinthine time” from Jalal Toufic’s Vampires: An Uneasy Essay on the Undead in Film, 2nd ed. (Los Angeles: Station Hill, 2003).

[iii] A traditional folk dance popular in the Persian Gulf region, where women in long, flowing dresses rhythmically sway and flip their hair in time with the music. Often performed at weddings and celebratory gatherings, this dance is a powerful expression of cultural heritage.

The exhibition begins and ends with the chaos of an after-party. In Puff Out M_2205_pink, :mentalKLINIK unleashes a fleet of robotic vacuum cleaners to roam a glitter-covered platform, drawing in and redistributing the glitter as they go (fig. 7). Elsewhere, the duo’s architectural and linguistic interventions scattered throughout the galleries push the boundaries of institutional space, extending the spirit of the rave: immersive and playfully unruly. During many internal discussions in the museum about the potential harm of glitter, one question lingered on my mind: Why are we so afraid of glitter? It is excessive and hard to contain, and it mirrors the very conditions of joy and collectivity that institutions often struggle to hold. Its refusal to stay still, like the rave, is what makes it so powerful.

This spirit carries over into Yasmine Nasser Diaz’s multimedia installation, which pays homage to the impromptu dance floors of domestic spaces through a highly personal bedroom scene (fig. 8). The installation features a two-channel video projection: One screen shows dancers clipped from social media; the other, footage of women-led protests. These images hover above protest ephemera, washed in pink neon and the shimmer of a rose-colored disco ball. Audiences are invited to step into the space and feel part of its intimate, defiant atmosphere, which will be activated through live performances.

The dismissal of rave and dance cultures as legitimate forms of cultural expression is nothing new. As Sarah Thornton argues in her 1996 book Club Cultures, dance floors have long been framed as escapist or unserious: music seen as banal, dancers as narcotized, conformist.[i] This disdain reveals deeper anxieties around collective joy, embodiment, and mass participation. Rave Into the Future challenges those assumptions, reclaiming the dance floor not as frivolous excess, but as a radical, curative space.

This exhibition is not a historical survey; it’s an experiment to reimagine what more a museum space can offer. This approach resonates with curatorial methodologies grounded in liveness and improvisation as proposed in art and dance studies.[ii] It is a partial offering, a gesture toward another possibility—a call to reimagine museums as civic, living institutions.

How do we interrupt Orientalist and trauma-driven narratives of the West Asian region? What would it mean to center joy, resilience, and complexity instead? Can museums hold space for collective imagination, for deep listening with feminist ears, for rethinking dominant truths?[iii] Can we remake our institutions from the dance floor up? Can we break the silence of the gallery?

This exhibition is a call for structural transformation. As Laura Raicovich writes in Culture Strike: Art and Museums in an Age of Protest, museums are not neutral; in fact, they are sites of struggle, and we cannot underestimate the power artists have to instigate change.[iv] The artists here resist categorization and bend time. They reject tragic heroism in favor of improvisation, collectivity, and joy. Through their practices, they mend what dominant art history has erased, ignored, or excluded.

I imagine a future shaped by the teachings of rave culture: a world that values experimentation over certainty, pleasure over control, softness over surveillance. A future built not on silence and separation, but on bass lines, breath, and bold new solidarities. Coming from a place of love, this exhibition invites you into the work of fearless undoing, committed and collective. Together, we can build institutions not as static monuments to the past but as gatherings: rhythmic, breathing, and always in motion.

[i] Sarah Thornton, Club Cultures: Music, Media, and Subcultural Capital (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1996).

[ii] For a discussion of curatorial strategies rooted in liveness and choreography, see Laura Preston and Stefanie Peter, eds., Assign and Arrange: Methodologies of Presentation in Art and Dance (Frankfurt: B Books, 2014).

[iii] I borrow the term “feminist ears” from Irene Revell and Sarah Shin, “Introduction: A Book of Echoes,” in Bodies of Sound: Becoming a Feminist Ear, ed. Irene Revell and Sarah Shin (London: Silver, 2024).

[iv] Laura Raicovich, Culture Strike: Art and Museums in an Age of Protest (London: Verso, 2021), 42, 88, 91.